The aim of this post is to put forward my interpretation of Hegel’s notion of Sittlichkeit[1] that he has described in his Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1820), and how this notion is problematic for individual autonomy. In this post I will employ the word ‘autonomy’ as the individual sovereignty for personal self-invention. This is in line with the Nietzschean notion of self-invention which is radically revolved around the emancipative powers of the individual.[2]

The aim of this post is to put forward my interpretation of Hegel’s notion of Sittlichkeit[1] that he has described in his Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1820), and how this notion is problematic for individual autonomy. In this post I will employ the word ‘autonomy’ as the individual sovereignty for personal self-invention. This is in line with the Nietzschean notion of self-invention which is radically revolved around the emancipative powers of the individual.[2]

I pay particular attention to the relationship between the individual and the community. Hegel’s notion of Sittlichkeit implies that individuals will find their self-realization in the communal ethical sphere. However, I will argue that it neglects those individuals who desire to distance themselves from the commune. As a result, the following question will be tackled: can man be truly autonomous in Hegel’s Sittlichkeit?

In order to state my position, I will firstly discuss Hegel’s conception of freedom and Sittlichkeit. From this perspective, I will subsequently assess why there is no space for individual self-invention in Sittlichkeit.

Freedom

It is necessary to first understand what Hegel’s notion of freedom is, since freedom is inextricably linked with autonomy.

It is worth noting that Hegel’s notion of freedom differs from the common-sense conception of freedom as the “ability to do what we please” (Hegel, §15, p. 27). He asserts that freedom is “the worthiest and holiest thing in man” (Hegel, §215, p. 273). The development of freedom, according to Hegel, is the aim of history, and man will only be free when he feels recognized and at home in a world that allows him to act in the interest of himself and simultaneously in the interest of everyone else in the world. Hegel explains how the individual’s pursuit of self-interest is protected in the first part of his Elements of the Philosophy of Right, named ‘abstract right’. Part two, under the heading ‘morality’, discusses how individuals feel at home in a world that permits them to take responsibility for their own self-interested pursuits. The third part, which is about Sittlichkeit, tells us that ethical life is guided with reason and when we act in accordance to this reason we will find freedom. (Rose, 2007, p. 105) Hegel believes in a teleological end of history where we will eventually enter a kingdom of freedom that is ruled with divine reason (Dyde, 1894, pp. 663-664). He writes that “[T]he state is absolutely rational” (Hegel, §257, p. 155) and that “[T]he state is the actuality of concrete freedom” (Hegel, §260, p. 160). Only in that world are there no obstacles anymore that limit man in his self-realization. Hegel stresses two important things about such a kingdom: one, only a state can provide the space of law in which individuals can live in freedom; and two, without mutual recognition there can impossibly be a confirmation of what I am and hence I cannot truly feel at home in the world, nor be free. This means that social and political institutions must acknowledge our needs as human beings and speak to those needs. Hegel thus has a different view of liberty than Rousseau who, when talking about the state, argues that “they have made an artificial man, which we call a commonwealth; so, also have they made artificial chains, called ‘civil laws’.” (Dyde, 1894, pp. 661-662) Man, in Rousseau’s eyes, becomes corrupted by society’s laws, and is faced with the dilemma of either pursuing his own self-interests and determining his own values or becoming corrupted by society which culture coincides with the interests of a particular class of people. However, he still believes that man can be free if he lives his own laws and desires what is moral. (Rose, 2007, p. 47) Hegel on the other hand, believes that the individual can only achieve absolute freedom when he is positioned in particular societal contexts. In Sittlichkeit, absolute freedom is achieved through the unity of the self with the society while the society operates on an objective rationality. The two antithetical conceptions of absolute freedom, one radically revolved around the individual’s self-government or self-invention and the other around the individual’s particular position in society, play a crucial role in this post. Later in the post, I will contend that there is no room for individual self-invention in Hegel’s Sittlichkeit and that the individual therefore cannot be truly autonomous.

Hegel distinguishes subjective freedom from objective freedom. Subjective freedom is the freedom enjoyed by the individual who critically reflects on his subjective desires and satisfactions in his actions or determinations. The objectively free individual is one who has the right determinations that are prescribed by reason. The absolutely free individual possesses both subjective and objective freedoms. Both freedoms are existent in Sittlichkeit, and can only be achieved through participation in Sittlichkeit. (Patten, 1999, pp. 35-36) Moreover, the social institutions in Sittlichkeit like the family, civil society, and the state are rationally endorsed by the individual who desires his rights. (Rose, 2007, p. 49) Hegel states: “man discovers within himself as a ‘fact of his consciousness’ that right, property, the state, etc., are objects of his volition” (Knox, Par. 19A, p. 29). At the same time, his desires are universal and serve all members of Sittlichkeit.

Sittlichkeit

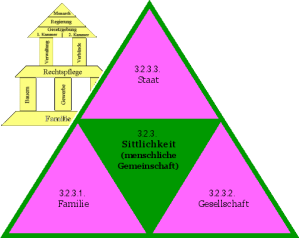

David Rose (2007) describes Sittlichkeit as an ethical sphere that “incorporates those values and norms which govern the subject’s practical reasoning and pre-exist him, deriving from his role in and his being a member of a certain society” (p. 107). The content of practical reasoning is embedded in customs in social institutions. A custom [Sitte] notably, is defined by Hegel not as a conduct created by the individual, but as one that has been habitually exercised by social groups and institutions such as the family or the state. Sittlichkeit is therefore a social or customary morality. Hegel believes that customs are important for the right relationship between state and individual, and that they are necessary for the maintenance of the individual’s vitality. Sittlichkeit provides the virtues and duties by which individuals should live. It engages the following three elements: one, the needs and desires that individuals pursue; two, the safeguarding of individual freedom in the market place; and three, the regulation of goods and practices in the market through police, courts and corporations. (Rose, 2007, p. 120) Alan Patten (1999) calls the Sittlichkeit thesis attractive, but also risky for being “under-determinate and unacceptably conservative” (Patten, 1999, p. 8). Robert Pippin writes that

“Hegel thinks he can show that one never ‘determines oneself’ simply as a ‘person’ or agent, but always as a member of a historical ethical institution, as a family member, or participant in civil society, or citizen” (Patten, 1999, p. 28).

Social institutions, according to Hegel, are therefore prerequisites for a person and his freedom. Within the social context we can become recognized as valuable and hence become fully human.

There are three spheres in Sittlichkeit: the family, the civil society, and the state. All three spheres allow individuals the following two things: one, allowing individuals to operate on personal choices and to seek self-interests; and two, allowing individuals to recognize their actions properly as their own while contributing to the society’s good and to feel at home. (Rose, 2007, p. 112) The idea that individuals can operate on self-interests while they simultaneously contribute to society is crucial in Hegel’s philosophy of rights. Through this process they can will the duties they should have towards society. I believe that it does have huge implications on individual autonomy. However, before individual autonomy in Sittlichkeit will be discussed, I will first examine the three spheres.

The family

Hegel writes that “[T]he family … is specifically characterized by love, which is mind’s feeling of its own unity”, (Hegel, §158, p. 110). Love is a feeling that overcomes the separation of the individual from his family unit. Hegel further states:

“[T]he first moment in love is that I do not wish to be a self-subsistent and independent person and that, if I were, then I would feel defective and incomplete. The second moment is that I find myself in another person” (Hegel, §158A, p. 261).

Love is “the rational social principle in the elementary form of a universal feeling” (Dyde, 1894, p. 660). Through love, the individual has renounced his independence and becomes certain of who he is. In the family, he is being recognized as irreplaceable and is endowed with a sense of his own importance. Hence, one achieves “in a family, … one’s individuality within this unity as the absolute essence of oneself, with the result that one is in it not as an independent person but as a member” (Hegel, §158, p. 110). The family therefore frees the individual and makes him feel complete. Love finds its actuality in marriage as the recognition of the union between man and woman. It furthermore liberates us from unstable sexual drives and directs our sexual energy to the duty of maintaining our families. It becomes also actualized in common ownership of family resources and the rearing of the child. However, the family is still solely based on the individual’s negation of his immediate desires for greater or nobler goods. (Rose, 2007, pp. 119-120) The civil society, on the other hand, does include mutual benefits from individual pursuits of self-interests.

The civil society

Hegel asserts that

“[T]he family is the first precondition of the state, but class divisions are the second. The importance of the latter is due to the fact that although private persons are self-seeking, they are compelled to direct their attention to others” (Hegel, §201A, p. 270).

The civil society is built on the people’s necessities to satisfy their needs. The system is determined by “desire itself rather than the content of these desires” (Rose, 2007, p. 129). The mutual benefits are the result of the individuals seeking personal prosperities. They are, albeit self-interested, united in a common market through trade and commerce. The desires of individuals are related in such a way that the market satisfies universal needs through the productive nature of the division of labour. It makes possible interpersonal existence. Hegel writes:

“[W]hen men are thus dependent on one another and reciprocally related to one another in their work and the satisfaction of their needs, subjective self-seeking turns into a contribution to the satisfaction of the needs of everyone else” (Hegel, §199, p. 129).

Productive cooperation on the market frees the individual from subsistence living. According to Hegel there are three classes in civil society: the agricultural class, the business class, and the class of civil servants. The agricultural and business class each works for the interest of their own class. The class of civil servants works for the universal interests of the community and “must therefore be relieved from direct labour to supply its needs, either by having private means or by receiving an allowance from the state which claims its industry” (Hegel, §204, p. 132). The classes will over time form uniform values and tastes so that its members can recognize themselves in it. Along with the values come responsibility and duties for the protection of their classes. To ensure that the free market does not isolate individuals, an administration of justice and rational law must be put in place (Hegel, §211, p. 134). For Hegel, law is objectified customs and “[B]y taking the form of law, right steps into a determinate mode of being” (Hegel, §219, p. 140). It can be made actual and it can be recognized “without the subjective feeling of private interest” (Hegel, §219, p. 140). It serves the universal good and it also requires the police to protect the laws for the sake of the community’s identity. Hegel writes:

“[T]he individual must have a right to work for his bread as he pleases, but the public also has a right to insist that essential tasks shall be properly done. Both points of view must be satisfied, and freedom of trade should not be such as to jeopardize the general good” (Hegel, §236A, p. 276).

The police should support the families to work for the general good and therefore has the right to provide public facilities for education, health services, and financial support. Hegel is aware that the tasks that he entrusts the public authority with, can “facilitate the concentration of disproportionate wealth in a few hands” (Hegel, §244, p. 150). When the share of wealth is not rightly balanced, it could lead to revolutions. In order to protect freedom and to prevent social nuisances, the civil community must acknowledge the universality of the state’s legislation and administration. (Dyde, 1894, p. 660) According to Hegel, the state is the highest form of social institution and people should live in accordance to its customs and be dutiful to it. By obeying state rules and assisting in the maintenance of the community, the individual will help safeguarding the conditions that are essential for his own freedom.

The state

According to Hegel, the state is the only means by which the society can be held subjected to the pursuit of the highest spirituality so that absolute freedom can be achieved for all (Kaufmann, 1953, p. 472). Hegel claims that “[T]he state in and by itself is the ethical whole, the actualization of freedom” (Hegel, §258A, p. 279 ). When discussing the state, Hegel is not referring to any existing states. He merely talks about the state in an ideal sense so there should be no misconception that none of our existing states are purely rational and have achieved absolute freedom (Avineri, 1972, p. 177).

In Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, Hegel argues that: “[F]or the everyday contingencies of private life, definitions of what is good and bad or right and wrong are supplied by the laws and customs of each state” (Hegel, 1830, p. 80). He furthermore states that “[T]he worth of individuals is measured by the extent to which they reflect and represent the national spirit” (Hegel, 1830, p. 80). However, Hegel makes clear that it is preposterous “to say that men allow themselves to be ruled counter to their own interests, ends, and intentions” (Hegel, §281A, p. 289). Instead, men are “directly linked to the ethical order by a relation which is more like an identity” (Hegel, §147, p. 106). The state is therefore based on its people’s rationality and their conscious will to absolute freedom. It implies that the state is not coercive as it is a natural extension of people’s will. (Avineri, 1972, p. 181) Without the state, freedom will be merely individualistic and subjective, resulting in people’s disregard of others’ desires.

People’s duties to the state are rooted in the sentiment of trust or what Hegel calls, the “political sentiment” or “patriotism”. However, the duties of the individual are both in his own interest and in the interest of the state. Even though duties “can appear as a restriction”, it is “liberation from the indeterminate subjectivity” (Hegel, §149, p. 107). Hegel writes:

“patriotism pure and simple, is assured conviction with truth as its basis … This sentiment is, in general, trust (…), or the consciousness that my interest, both substantive and particular, is contained and preserved in another’s (i.e. in the state’s) interest and end, i.e. in the other’s relation to me as an individual. In this way, this very other is immediately not an other in my eyes, and in being conscious of this fact, I am free” (Hegel, §268, p. 164).

The sovereign, according to Hegel, should be a monarch as he is the embodiment of rationality, truth and constitutionality. He acts as the absolute decider and is the personhood of all people.

Individual autonomy in Hegel’s Sittlichkeit

Having explained Hegel’s Sittlichkeit thesis, I will now contend that individuals cannot become truly autonomous in Sittlichkeit.

So far it has become apparent that Hegel has posited individuals inside communal entities that he deems necessary for the progression of individual freedoms. The notion that individuals find their absolute freedom in social institutions that correspond to their subjective needs and desires is problematic. According to Hegel, individuals are free under conditions where they work for the collective good without giving up their particular identities. However, we do often not understand who we are, nor do we understand our subjective desires, so how can we know for sure that the actions we take are expressions of our identity? I would contend that the only way to understand ourselves is through self-reflection and self-invention. Sittlichkeit, unfortunately, restrains individuals in their self-invention, because communal entities hold authority over customs and moralities. Individuals, according to Hegel, have obligations to abide by the customary moralities of his communes: the family, civil community, and the state. However, autonomy, defined as the condition to give oneself one’s own laws, cannot be embedded in such communes. Instead, autonomy is the result of individualistic endeavours and is often gained as a result of the rejection of communal customs, because they hold us in bondage. The morality of customs relates to “the age, the sanctity, and the unquestioned authority of the custom” as Friedrich Nietzsche has explained in The Dawn of Day (1881) (Section 19, pp. 28-29). Sittlichkeit is predicated on a customary morality that pre-exists the individual and holds moral authority over him before he was even born. The individual is then still chained to the historical morality of his people, making him more similar to people in the same community. When others have authority over us in claiming what is right and wrong, then there is little room left for us to invent our personal morality. I agree with Hegel that “every one is a son of his time” (Hegel, Preface, p. 11). However, individuals should also have the autonomy to divert from this history and create their own distinctive personhoods. The family and any other ethical unit can be abusively restrictive to individual autonomy, stripping people from their freedom of self-invention. The resistance that the autonomous individual will face is grounded in the community’s mistrust of that what is different. Nietzsche (1886) maintains in Beyond Good and Evil that “self-reliance is almost felt to be an insult and arouses mistrust; the “lamb,” even more the “sheep,” gains in respect” (Section 201, p. 114).

The second reason why individuals cannot achieve true autonomy in Sittlichkeit, is due to its emphasis of self-limitation. According to Hegel, the individual has to limit himself in order to become liberated in the social spheres of the family, civil society and the state. In a paragraph on the people who enter into marriage, he writes for example that they

“renounce their natural and individual personality to this unity of one with the other. … their union is a self-restriction, but in fact it is their liberation, because in it they attain their substantive self-consciousness” (Hegel, §162, p. 111).

For Hegel, the individual is a subject of his community and his experience of selfhood is dependent on the recognition of others. However, I would like to desubjectivize the individual, pull him free of himself and his community, make him the source of all morality, and prevent him from being the same.[3] The individual can only be truly autonomous if he rejects communal customs so that he can invent his own morality. Hegel says that in “intersubjective actions, we follow the appropriate moral norms” and that we therefore “recognize each other reciprocally as subjects of unique value to each other, because without the other we would feel deficient and incomplete” (Honneth, 2001, p. 65). The self-worth of individuals is in my opinion too dependent on his community. Freedom, I believe, means feeling at home with oneself, and not so much feeling at home in the world as Hegel would contend. Self-limitation is apparent in, for example, the family which is based on individual self-negation for the family unity. The individual has to negate his “immediate desires for those of the greater good (nobler ones)” (Rose, 2007, p. 117). Obedience and autonomy are paradoxically joined in Hegel’s Sittlichkeit thesis to bring forth an absolutely free individual. Furthermore, I believe that the state cannot restrict people in their desires. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche calls the state the “coldest of all cold monsters” and argues that the “idolaters” of the state “hang a sword and a hundred inordinate desires” above the people. It can make its people poorer or richer, but it is an institution that desires power and “first of all that lever of power, lots of money”. (Nietzsche, 1883-1885, pp. 36-38) The state will thus perpetuate non-restrictive lust for power as it will attract individuals to resist customary ethical life in order to use the state for their advantage.

The third argument why individual autonomy cannot be obtained in Hegel’s Sittlichkeit thesis is because faith in the state implies a faith in herd morality.[4] Hegel’s faith in social institutions is especially obvious in assertions like “[T]he state is the actuality of the ethical Idea” (Hegel, §257, p. 155) and “[T]he march of God in the world, that is what the state is” (Hegel, §258A, p. 279). The radical belief in the state as the provider of solid ethical values seems similar to the radical belief in religion. The only difference between both faiths is that one is a zealous belief in the state and its rationality, whereas the other is a passionate belief in a higher spiritual power. Both are however grounded in the belief in external entities; either the community to which the individual belongs or God. Under both circumstances, the individual negates his personal morality and praises herd morality as both prescribe customary group moralities. By zealously believing in the state, albeit a rational one, the individual will run the risk in subverting his own morality and therefore his personal autonomous ethical well-being for this higher ‘religion’ (the state) that is composed of communal dogmas and traditions. Moreover, Hegel’s emphasis on duties towards the state[5] in combination with the self-negation for the greater good may sound plausible ideally, but it is a frightening notion for individual freedom in practice. How can Sittlichkeit make sure that monarchs with illustrious powers will not abuse its members’ duties to the state?

Having explained why individuals cannot attain true autonomy in Sittlichkeit, I will discuss how autonomy is expressed. The autonomous person, I believe, will detach himself from customs and impose unto himself his own moral rules. In other words, he is able to become a self-determinate atom that does not necessarily have to find his freedom through the recognition by an other. All that suffices for his autonomy is his personal recognition of himself as an individual who can and who must invent himself. Since the individual is the source of self-invention, he is continually threatened in a world that imposes codified customs in the form of communal laws. Therefore the autonomous individual has to reject any position that society has molded for him. Instead, his place in society must be created by himself. One may argue that communities like the civil society and its market place are essential for individuals to be recognized and to thrive beyond basic necessities, and that this is freedom. Nevertheless, I would like to stress the importance of choice for self-invention and voluntary association. Individuals should be free to voluntarily accept society and its laws; free to accept and reject duties towards the state. The individual exhibits autonomous behaviour in his choices. Therefore, the power to choose is the ultimate source of autonomy. In Sittlichkeit, the individual is presupposed to be in unity with the family, civil society, and the state. All these social entities restrict his choice to dissociate himself from his communes.

Conclusion

This post has attempted to explain why man cannot achieve true autonomy in Sittlichkeit. The Sittlichkeit thesis can be attractive from an idealistic perspective, because it involves the community’s rationality and dialogue in order to give its members self-certainty so that no one is left out and everyone is included into a grander purpose in life. However, there is a danger that individual members are stripped from self-inventive powers, because they are pushed into moral directions by the customs of their communities. The individual should be fearful for moral conformism in Hegel’s Sittlichkeit as it negates individual autonomy. In addition, Sittlichkeit restrains individuals in their self-invention. Ultimately, the individual’s zealous belief in the rational state is actually appraisal for herd morality in Nietzschean terms.

Footnotes

[1] Michael Inwood’s A Hegel Dictionary (1992) defines Sittlichkeit as ‘ethical life’ and ‘social or customary morality’ (p. 91).

[2] Nietzsche writes in The Gay Science (1882): “[W]e… want to become those we are – human beings who are new, unique, incomparable, who give themselves laws, who create themselves” (Section 335, p. 266).

[3] Michel Foucault calls it the “the project of desubjectivation” (Gutting, 2010, p. 29).

[4] Nietzsche often refers to the majority as the herd. He argues that the herd is mediocre and condemns self-inventive persons. (Nietzsche, 1883-1885, p. 16)

[5] Hegel states that the individual’s “supreme duty is to be a member of the state” (Hegel, 1820, §258, p. 156).

Bibliography

Avineri, A. (1972). Hegel’s Theory of the Modern State. London: Cambridge University Press.

Dyde, S.W. (1894). Hegel’s Conception of Freedom. The Philosophical Review, 3, 655-671.

Gutting, G. (2010). Foucault, Hegel, and Philosophy. In T. O’Leary & C. Falzon (Ed.), Foucault and Philosophy (pp. 17-35). Oxford: Blackwell.

Hegel, G.W.F. (1830). Lectures on the Philosophy of World History. (H.B. Nisbet, Trans.) New York: Cambridge University Press.

Honneth, A. (2001). The Pathologies of Individual Freedom. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Inwood, M.J. (1992). A Hegel Dictionary. Oxford U.a.: Athenaeum Press.

Kaufmann, W.A. (1951). The Hegel Myth and Its Method. The Philosophical Review, 60, 459-486.

Knox, T.M. (1967). Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. London: Oxford University Press.

Nietzsche, F.W. (1886). Beyond Good and Evil: prelude to a philosophy of the future. (W.A. Kaufmann, Trans.) New York: Random House.

Nietzsche, F.W. (1881). The Dawn of Day. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Nietzsche, F.W. (1882). The Gay Science: with a prelude in rhymes and an appendix of songs. (W.A. Kaufmann, Trans.) New York: Random House.

Nietzsche, F.W. (1883-1885). Thus Spoke Zarathustra: a book for all and none. (T. Wayne, Trans.) New York: Algora Publishing.

Patten, A. (1999). Hegel’s Idea of Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rose, D. (2007). Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: a reader’s guide. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.